I’ve spent almost my whole life waiting for my first heart attack.

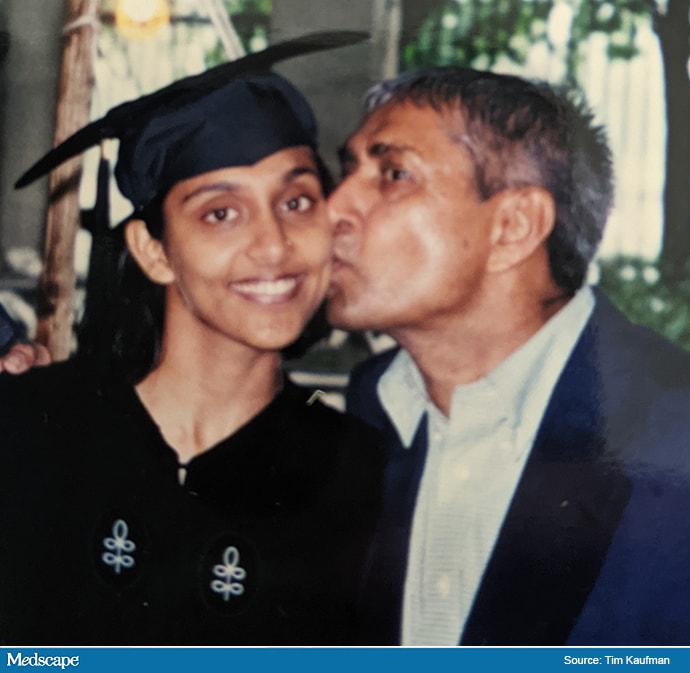

My dad had his first one in his early 50s. Then came quadruple bypass surgery. Four blood vessels in his heart had become clogged with thick, waxy sludge. Surgeons snipped parts of a vein from his left leg, stitching it around the blockages.

I remember the jagged slit: four cuts stretching from thigh to ankle where the vein had been. And the chest wound left by the bone saw that the surgeons used to pry open his sternum to reach the heart. That scar never fully healed. It puckered, darkened, and stood out to me like a harsh warning.

Dad wasn’t alone. Every few months, we’d visit friends who’d also had bypass surgeries. The men would unbutton their shirts to compare scars.

I knew a healthy lifestyle and medications might delay my heart attack. But I never really believed that I could prevent it. I felt at the mercy of my genes.

Someday, I would shift from being healthy to sick.

The author at her college graduation with her father, Ramanaresh Pathak.

This was a big reason why I became a doctor: to help my patients (and myself) stay well for as long as possible. It was about holding off disaster.

But in all my years in practice, I never really saw anyone get better from heart disease or diabetes just by taking my prescriptions. Their lists of medical problems, medications, and side effects grew. And my frustration and disappointment deepened.

This hopeless feeling is something I had in common with Tim Kaufman. He’s not my patient, but he calmly tells me his story via Zoom. He used to feel just like me. He saw an early death as inevitable, despite more than a decade of care from a host of doctors.

Until he didn’t.

Downward Spiral

In his 20s, Kaufman was diagnosed with a painful disorder. This led to a sedentary life and addiction to opioids, alcohol, and fast food. By his late 30s, he took more than 20 prescription drugs to manage his chronic pain, blood pressure (BP), and cholesterol.

Still, his BP and heart rate were dangerously high. His blood pressure reached 255/115. (Normal is less than 120/80.) His heart rate clocked in at 125 beats per minute. (Normal ranges between 60-100.)

Kaufman weighed more than 400 pounds. He doesn’t know the exact number because his doctor’s office scale didn’t go that high.

“I had gotten real sick, real fat, and real addicted ― real quick,” Kaufman says.

Eventually, he began to believe that this was the body he was given, this was his DNA, and he’d just have to accept the misery.

When his doctor tried to add yet another medicine to the mix, Kaufman threw the prescription in the trash on his way out of the office. Finally at a breaking point, he felt that his doctor couldn’t help him.

Kaufman set a sobering goal: to delay his own funeral for as long as possible. And he wrote himself a prescription: “Get up from the chair two times tomorrow.”

Last-Chance Plan

Kaufman has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), a genetic connective tissue disorder. He’d always had flexible joints. As a kid, he did “circus tricks” to entertain his friends.

His condition got worse. Something as mild as a loud sneeze would dislocate his shoulder.

As an adult, newly married and with a growing family, Kaufman had his first joint surgery. Afterward, his doctor said the procedure had been very hard to do. Instead of tough fibers that keep the shoulder in place, Kaufman’s tissue was loose, weak, and stretchy, like chewing gum.

To protect his joints and avoid more surgeries, Kaufman was told to limit physical activity. Get a desk job, he recalls his doctor saying.

That was when he got his first taste of opioids. The mild chronic pain he’d always had would fade for a few hours, only to roar back when the meds wore off. Working with his doctor, he upped his doses until he was on opioids 24-7.

With strict limits on activity and worsening chronic pain, Kaufman started to self-medicate with vodka and fast food. The diseases of a sedentary life (high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and high blood sugar) began to pile up. So did the medications to treat them. And he needed crutches and costly custom-made knee braces.

But there was something even more painful than the physical suffering. It was seeing pity in the eyes of Heather, his wife and high school sweetheart.

Every task he had to quit, like mowing the lawn, landed on Heather’s to-do list. Their kids didn’t expect much from him either. They just knew that “Dad’s sick.”

At 38, Kaufman was in such bad shape that his doctor wouldn’t OK gastric bypass surgery for weight loss. It was too risky for someone with so many out-of-control medical problems.

Desperate to not die, Kaufman only asked his muscles to pick him up out of his chair twice one day, then three times the next. After that became manageable, he started to walk on a trail near his home.

He couldn’t have dreamed up a better, more personalized medicine.

How Exercise Helps

Our muscles and fat cells aren’t silent bystanders that bulk up or break down in an endless tug of war between food and exercise. They make messenger chemicals that go to parts of the body both near and far. They can turn on and off thousands of genes, raise or lower inflammation, and rev up or slow down metabolism.

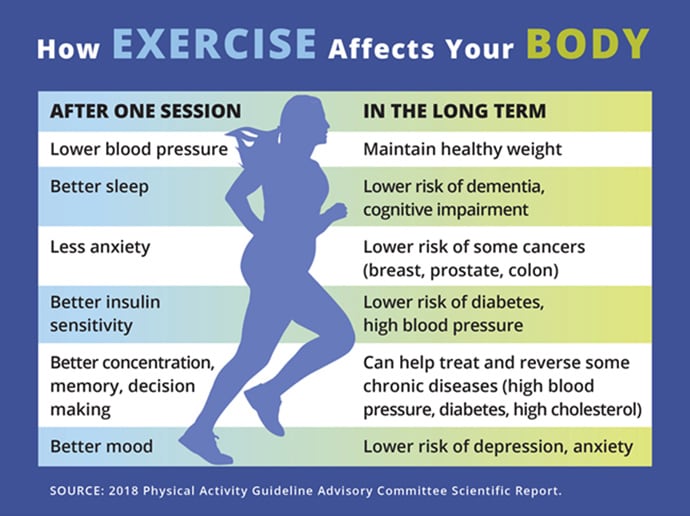

Physical activity does much more than just strengthen muscles. Moving your body prevents blood vessels from getting damaged and clogged. That helps prevent heart attacks, strokes, and even some types of dementia.

In a very real sense, our muscles make our own precision medicine. It’s a targeted cascade of chemicals that help prevent disease, repair injury, and help us live longer, healthier lives.

This medicine is perfectly calibrated, working at the right time on the right target at the right dose. As a doctor, there’s no better medicine in my arsenal.

Exercise is as good as medication at preventing diabetes and heart disease in at-risk people. And for stroke recovery, exercise is more effective than drugs. Researchers learned this by analyzing data from more than 300 randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard for studies.

Chronic conditions not only kill in the long run, they also make death more likely in the short term. COVID-19 made that painfully clear. Again, exercise might help here, too. In one study, researchers checked the activity level of nearly 50,000 people who later got COVID-19. Those who were consistently active were less likely than inactive people to be hospitalized or die of COVID-19.

Being active also helps to prevent certain cancers. The best data is for breast, colon, and prostate cancers. Studies show that regular physical activity can lower the risk of colon cancer between 17% and 30% and breast cancer risk by 20% to 30%.

Right now, you’re just one brisk walk away from starting to get those benefits.

Your Body on Exercise

When you head out on that walk (or do any other type of moderate exercise), your body unleashes an army of billions of immune cells, some aptly named natural killer cells. Within an hour, these cells filter out of the bloodstream and seep into organs throughout your body. They find and destroy dangerous intruders (think viruses) and defective cells (think cancer).

Exercise may also help you avoid conditions like dementia and Parkinson’s, which don’t have effective drugs to prevent, reverse, or cure them.

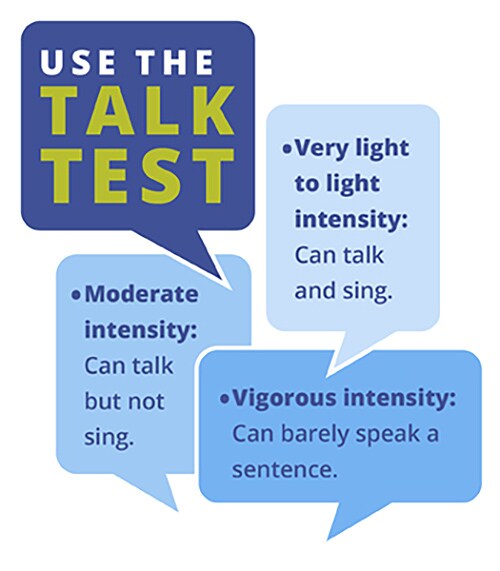

For Parkinson’s, high intensity interval training (HIIT) may improve brain cell activity and delay the worsening of the disease. HIIT switches between short bursts of intense exercise and less-intense recovery periods. For instance, you might sprint for a short time, and then walk, and then sprint again. HIIT is now gaining attention from researchers as a way to improve general health, not just shred fat and make you look ripped.

Here’s what’s going on inside when you’re active. After just 2 minutes, thousands of molecules start to shift. Within 10 minutes, key chemicals rise or fall.

In one study, some of these changes lasted for minutes. Others stayed for at least an hour. A second study backed that up.

This affects genes, immune cells, inflammation, blood sugar, fat, metabolism, tissue healing, inflammation, and more.

Scott Trappe, PhD, of Ball State University leads a team of scientists studying exactly how physical activity boosts health. It’s a deep dive into the biology of active and sedentary people, funded by the National Institutes of Health.

But you don’t need to be a scientist to understand the core concept. It’s the power to change your body ― down to your cells and molecules ― just by moving. Trappe calls it “plasticity,” meaning that how your body is right now isn’t how it has to always be.

His advice: Don’t think of exercise as just a tool to burn off calories. Make it part of your life because the more often we use our muscles, the more often we send those waves of molecular messengers out through the bloodstream to refresh our entire system.

Check out the results you get after one workout, and over time when you’ve made it a habit.

Many people hate to exercise. But that can change once it’s a habit and you start to feel better. It helps if you choose something you like to do and can do with other people.

Kaufman found that the more he moved, the more movement his body craved. He set new goals to climb stairs, hike mountains, and run more races than he now remembers, a decade after his health crisis. Rows of medals hang behind him on Zoom as he tells me his story.

Only Good Side Effects

With every step, Kaufman pictured leaving a stamp of gratitude on the ground beneath his feet, thankful for each new day of life. It became such a powerful mental image that he had his “gratitude stamp” tattooed to his calf.

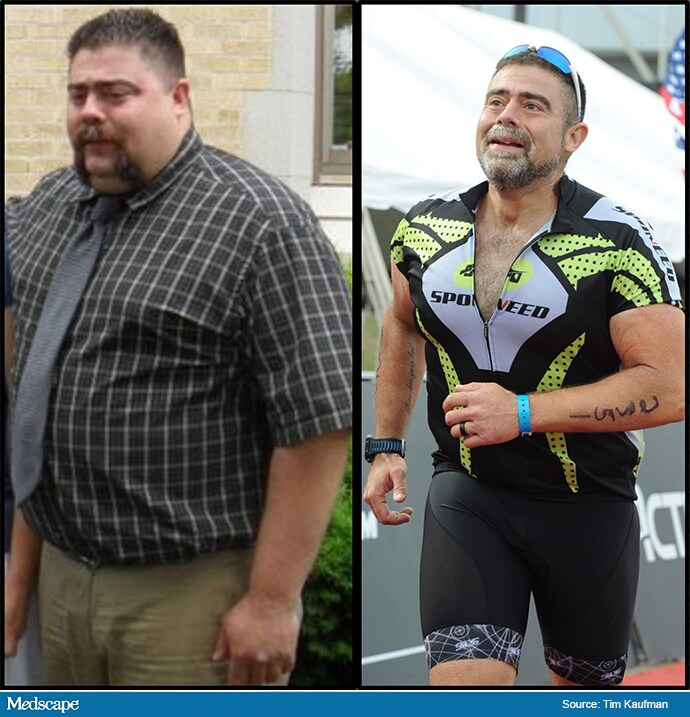

BEFORE: “I had gotten real sick, real fat, and real addicted ― real quick.” AFTER: “I wasn’t running away from anything anymore.”

Slowly, his muscles could handle the work that his connective tissue couldn’t. As he grew stronger, Kaufman could walk without his crutches and no longer needed his knee braces.

The weight he lost from a dramatically improved diet stayed off. He could finally sleep through the night without restless, painful tossing and turning. With his doctor’s blessing, his long list of prescriptions melted away.

He no longer needed the opioids, alcohol, and fast food. They had never felt like enough to get him to the next hour. Kaufman had more energy than he could use in a day.

“I wasn’t running away from anything anymore. I was running to more adventures with my wife.”

Clearer Thinking, Better Mood

When you’re active, your whole body perks up, including your brain.

Regular activity sharpens attention, memory, and decision-making. It can slow the shrinkage in brain volume that happens with age. It may also grow the hippocampus, the memory-making part of the brain.

Your mental health also improves.

When you work out, you get a higher level of dopamine, a chemical in the brain’s reward system. And your body releases its own endocannabinoids — like those found in cannabis. That may partly explain “runner’s high,” the mood boost that can follow a workout. It all adds up to less anxiety, fewer blues, and more positive feelings.

For Kaufman, the gains spilled over to his family. His wife, Heather, became an avid runner. Kaufman chokes up with emotion as he recalls seeing Heather’s face as he finished his first race. Her eyes were filled with pride. Pity was long gone.

But for all the life-changing benefits, has your doctor ever said more to you than, “Try to get some exercise?”

Underwhelmed by Medicine

Primary care doctor Robert Sallis, MD, didn’t treat Kaufman. But he thinks doctors can help many more people have that kind of success by doing three simple things.

Dr Robert Sallis

-

Ask about exercise at every appointment.

-

Note it in your health records as a vital sign, like blood pressure and temperature.

-

Prescribe exercise as a fundamental part of every treatment plan.

“I feel like I’m underwhelmed every day in medicine by what we do, that, ‘This is all we got? This is as good as it is?’ Especially with medication,” says Sallis, who chairs the American College of Sports Medicine’s Exercise is Medicine Initiative.

He sees exercise as safer, more powerful, and more cost-effective than almost anything else that doctors prescribe. Similarly, Kaufman’s doctor once told him that 70% of the people in his waiting room wouldn’t be there if they just walked briskly for 40 minutes every day. In fact, about 1 in 10 early deaths worldwide caused by diseases that aren’t contagious can be traced back to physical inactivity, researchers reported in The Lancet.

But the message often falls through the cracks.

Doctors and other health care professionals routinely fail to prescribe exercise or emphasize physical activity in preventing and treating chronic disease.

One study found that only 1 in 3 patients were told how important physical activity is to treat high blood pressure. Another showed that only 18% of people with diabetes were offered counseling about the benefits of exercise.

Sallis finds that shocking.

“If you look at any guideline, from the guideline on low back pain to rheumatoid arthritis, to breast cancer and colon cancer, to heart disease … one of the first ones is, patient physical activity is helpful. We always skip right over that to the first drug.”

“Why wouldn’t we, as the first-line treatment, prescribe exercise rather than medication?” Sallis asks.

The answer is partly about the person doing the prescribing.

Walking the Walk

The more active your doctor is, the more likely they are to spend time counseling you about exercise as a treatment option versus going straight to meds.

That certainly was true for me. Early in my medical career, I’d give a brief nod to my patients about diet and exercise. But I had to spend most of the precious time in appointments explaining and managing an ever-growing list of prescriptions.

This isn’t to say that medications and procedures are never needed. They’re often essential and lifesaving. Never quit or adjust a prescription without talking to your doctor first.

As a doctor, my goal isn’t to get every patient off medications. It’s to optimize their health, whether or not prescriptions are necessary. And to do that, you need the foundation of a healthy lifestyle.

This also isn’t about blaming or shaming people who develop chronic diseases or who must take medications. Many other factors are involved, like genes and access to good medical care, a safe place to be active, and nutritious food. Sleep and stress management also matter. And sometimes we lead a healthy life and still get sick.

The key is to recognize that taking control of your lifestyle can protect you much more than you might think.

Exercise Doses

It doesn’t take much to start to boost your health. ANY amount of activity is better than nothing. Even short bursts of less than 10 minutes make a difference. It all counts.

For most people, the goal should be to work up to at least 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity exercise, like a brisk walk. You could split that into 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week.

If you can handle harder activity like running, 75 minutes a week is enough. U.S. physical activity guidelines also recommend doing muscle-strengthening exercises at least twice a week.

The guidelines are universal. “They’re the same in the U.K., Australia, Europe, on and on and on,” Sallis says. “We all say the same thing. You can’t get five people to agree on what’s a healthy diet. But when you talk about physical activity levels, there’s no argument.”

Still, fewer than 1 in 5 U.S. adults meet these guidelines. Would a prescription from your doctor help?

Prescribing Exercise

It’s one thing to write an exercise prescription, and another to make sure that people follow it.

“I had tried the prescription thing in the past,” says cardiologist David Sabgir, MD. “But honestly, I [wasn’t] seeing a lot of success with that.”

Sabgir felt very comfortable talking to his patients about the benefits of exercise. But he grew frustrated with how hard it was to help people actually do it.

Exasperated, he invited a patient to take a walk with him. That was in 2004. It’s been a “beautiful cascade from there,” Sabgir says.

He founded Walk with a Doc (WWAD), a nonprofit group that pairs patients with doctors for walks. With chapters across 34 countries, WWAD hosts 130,000 walks per year.

For doctors, it’s like directly observed therapy, in which we watch patients take medications exactly as prescribed. Sabgir credits WWAD’s success not just to exercise but also to group bonding and being outside.

Talking about exercise or recording it as a vital sign isn’t enough, says Cate Collings, MD, president of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine. She says doctors need to get specific, giving patients an exercise prescription that spells out exactly what to do, how long, and how often, for their particular condition.

Exercise science is moving in this direction. For example, there is growing evidence that an exercise dose of 300 minutes per week can help people with type 2 diabetes to reverse their condition and potentially come off medications. That same dose also helps maintain weight loss.

As good as it is, exercise is just one part of a healthy lifestyle. Nutrition is also key. So are avoiding toxins like drugs and tobacco, getting restorative sleep, practicing gratitude, and forging close social ties, Collings says.

Changing From the Inside Out

Kaufman’s DIY transformation unwittingly hit on almost everything Collings recommends. Switching to a plant-based diet provided energy to be more active. No longer on any prescription drugs, he considers food and activity his medicine.

It didn’t happen overnight, and it’s not about being perfect.

Kaufman confesses that when he had cleaned up his diet and ramped up his activity, he still chewed tobacco. Tackling one habit at a time snowballed into other positive changes.

As we talk, I think about how my own habits slipped during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of my day isn’t active. I’m eating worse than I have in years. I feel anxious.

And yet, in the back of my mind, I wonder if I can still turn things around and prevent that heart attack I’ve always dreaded. My dad made some lifestyle changes in his 70s, including more movement, and is doing well at 84. It truly is never too late.

I share a little about this with Kaufman. He tells me to go out and just move my muscles and breathe the air and not to think of it as exercise. I envision thousands of chemical messengers flooding through my bloodstream, reaching every organ from my brain to my toes.

Heather and Tim Kaufman

He reminds me, “All you have to do is move a little more than you did yesterday.”

For him, the weight loss wasn’t what transformed him. It’s his newfound sense of joy and adventure, which no pill or injection can deliver.

“It’s not about the before and after photo,” Kaufman says. “If I could make you feel how I feel … you would switch in a minute.”

Source: Read Full Article