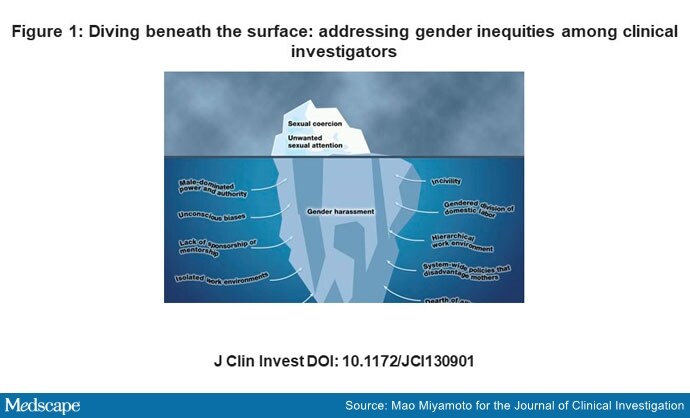

Sexual harassment in medicine is like an iceberg, with the most obvious behavior ― unwanted sexual advances and sexual coercion ― visible at the tip but involving a larger, mostly hidden, body of other factors below the surface, says Pamela Kunz, MD, of Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut.

“We’ve all heard of sexual misconduct or sexual coercion. But the large majority of sexual harassment falls under the surface. It has long gone unrecognized,” she told Medscape Medical News.

Kunz, a gastrointestinal oncologist, is also vice chief of diversity, equity, and inclusion in medical oncology at Yale’s School of Medicine.

She has previously been at Stanford University, in Stanford, California, but left after 19 years, saying that “the accumulated gender discrimination and harassment had taken their toll.”

Kunz was talking about sexual harassment in medicine at the recent American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2021 annual meeting, acting as a discussant for a new survey of sexual harassment in oncology workplaces. That survey found that 70% of physicians had experienced sexual harassment in the previous year.

This survey, conducted in 2020, is “practice changing” in part, Kunz commented, because becoming aware of the data is a “step in the direction to enact real change.”

The iceberg analogy comes from an influential 2018 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). It helps to portray the dynamics of sexual harassment ― so that scientific and medical professions can address it, she explained.

The predominant hidden component of sexual harassment is gender harassment ― nonverbal or verbal behaviors that are hostile, objectifying, and excluding of or conveying second-class status about a gender. Such harassment has been described as being comparable to a “1000 paper cuts” or living in a sustained, intolerable environment, said Kunz.

But “what is in the water” around the harassment iceberg is also very important, she continued. “Yes, we need to address the actual aspects of gender harassment…but part of it is looking at what’s in the environment and contributing to harassment,” Kunz explained.

Environmental factors tied to harassment include male-dominated power, incivility, and policies that are disadvantageous to mothers (see figure 1), as well as uninformed leadership and mentor/advisor relationships that potentially punish whistleblowers.

“What can we do about it?” Kunz asked the ASCO audience.

At a minimum, a good first step for organizations interested in addressing sexual harassment is to collect data, Kunz said. “We need to track and measure in order to know what difference we’re making. If you don’t measure it, you don’t know what’s happening and you can’t do better.”

Kunz also placed the problem in academia, including medicine, in sobering context. Among United States workplaces, academia has the second highest rate of sexual harassment, after the military.

“Cup of Coffee” Conversation Reduces Complaints by 83%

Kunz reviewed a “professionalism” program developed at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tennessee, that hinges on peer intervention. The program has been implemented at 180 medical centers and hospitals across the country.

“Trained physician ‘peer messengers’ meet with physicians who have been identified as having unprofessional behavior in what is described as a ‘cup of coffee conversation’ intended to be an initial, nonthreatening talk with an individual about a first offense,” explained Kunz.

These initial conversations have been demonstrated to reduce future co-worker complaints by 83%, she emphasized.

The program, known as the Co-Worker Observation Reporting System, digitally stores harassment-related patient complaints and co-worker concerns that are subsequently read by trained coders, who produce reports. Next, an algorithm generates an individual’s risk score, which, after being reviewed by staff physicians and nurse practitioners, may trigger a peer intervention.

Kunz also highlighted the importance of advocacy programs and cited a program at the Ohio State University (OSU) as exemplary.

Funded by the National Science Foundation, the Advocates and Allies for Equity Initiative was launched at OSU in 2016. It has the important feature of changing the institutional climate by “enhancing men’s engagement in gender equity work.”

Men at OSU who “already have a substantial record of supporting women staff and faculty” lead the program. Those men facilitate group conversations with other men to expose them to ways to be allies in gender equity. Evidence-based knowledge, skills, and strategies are shared, she explained.

The approaches outlined by Kunz in her presentations have similarities to proposals put forward in a 2020 report in the Harvard Business Review, authored by sociologists Frank Dobbin, PhD, of Harvard University, and Alexandra Kalev, PhD, of Tel Aviv University, in Israel.

Currently, the most commonly used tools to address sexual harassment ― mandatory training programs and formal grievance procedures ― date from the 1990s, the authors point out. They don’t work and are “managerial snake oil” prompted by legal concerns, the pair assert.

More appropriately inspired programs have evolved in recent years and are effective, say the authors of the report. As with the examples described by Kunz, these include peer interventions and getting men involved as agents of positive change.

More on the Importance of Environments

On the underside of the iceberg are workplace factors that “silence targets of harassment” and others that facilitate inappropriate behavior, Kunz explained, referencing the NASEM report.

In terms of silencing targets, there are four outstanding factors.

Most importantly, targets of harassment have their futures entwined with advisors and mentors; in short, a complaint can halt career advancement. But there is also, in some fields, a “macho” culture that is intimidating. More commonly, there are networks in which rumors and accusations spread. Finally, systems for advancement (the so-called meritocracy) only look for successes and do not measure declines in morale or productivity losses. In short, an environment may be toxic for many, but that is not important as long as some members excel.

In terms of aiding and abetting sexual harassment, there are five major factors at workplaces.

The list includes a perceived tolerance for harassment; male-dominated settings; a hierarchal power structure; and symbolic (but not vigorous) compliance with federal statues that prohibit employment discrimination and sex-based discrimination in education. Finally, uninformed leadership also increases the likelihood of harassment.

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2021: Discussion of abstract 11001. Presented June 4, 2021.

Nick Mulcahy is an award-winning senior journalist for Medscape. He previously freelanced for HealthDay and MedPageToday and had bylines in WashingtonPost.com, MSNBC, and Yahoo. Email: [email protected] and on Twitter: @MulcahyNick.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article