The number of children entering institutions should be gradually reduced to zero, according to a new report published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health and The Lancet Psychiatry journals. The authors call for every effort to be made to minimise children’s exposure to institutional care.

To help achieve this, they recommend strengthening and supporting families to reduce the need for separation. They also propose ways to ensure child safety, to protect children without parental care by providing high-quality family-based alternatives, and to strengthen systems for the care and protection of children.

Led by 22 of the world’s leading experts on reforming care for children, the Commission includes a review and meta-analysis of the effects of institutionalisation and deinstitutionalisation on children’s development, and makes 14 policy recommendations addressed to policymakers at all levels. The Commission was chaired by Professor Edmund Sonuga-Barke, Professor of Developmental Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience at King’s College London who leads the English and Romanian Adoptee (ERA) Project. The report is published in two parts, alongside an Executive Summary, and four Commentaries from leading experts in the field.

Writing in the Executive Summary of the report, Niall Boyce, Editor-in-Chief of The Lancet Psychiatry, Jane Godsland, editor-in-chief of The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, and Commission Chair Professor Edmund Sonuga-Barke, King’s College London, UK, say: “The global intent to provide optimal care for separated children has never been greater. Momentum to move children from institutions and into families is building, led by welcomed evidence and practical leadership from many sectors within child health, child protection, and social welfare. It is essential that governments, voluntary organisations, and health and social care professionals work together so that action is not taken precipitately, with potentially unintended adverse consequences, but is instead timely, sustainable, and child-centred.”

In 2015, between five and six million children were estimated to be living in institutions (eg, orphanages, residential homes) in 137 countries worldwide [1]. According to the authors of the new report, while the number appears to have decreased in recent years in some countries, it appears to have increased in other countries over the last 30 years largely due to the HIV crisis.

The effects of institutionalisation and recovery

In the first part of the commission, published in The Lancet Psychiatry journal, the authors reviewed evidence of the effects of institutionalisation, addressing two main questions: whether growing up in an institution is detrimental to development compared with growing up in a family or family-like environment, and whether deinstitutionalisation leads to recovery. They reviewed 308 studies from the past 65 years, which were conducted across 68 countries and involved over 100,000 children.

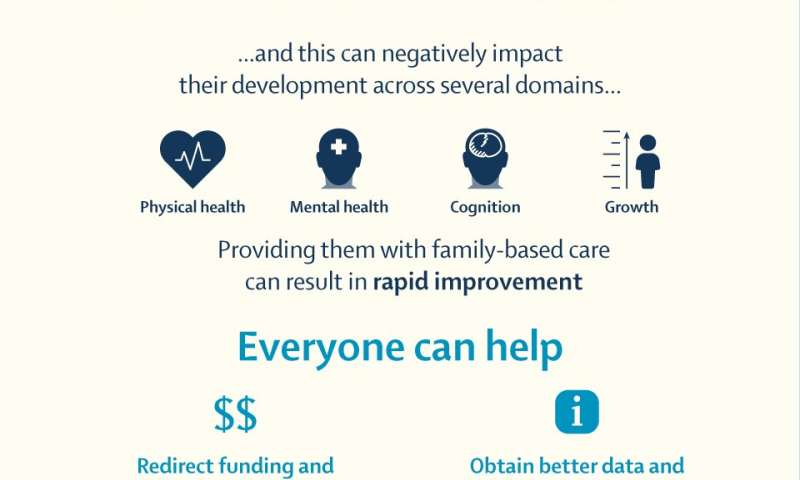

The study found strong negative associations between institutional care and children’s development, especially in relation to physical growth, cognition and attention. The authors also found significant, but smaller, negative associations between institutionalisation and socioemotional development and mental health.

The authors warn that these effects may be especially harmful to babies aged six to 24 months, and that longer stays in institutions are associated with larger developmental delays. These effects can be rapidly reversed in the years immediately after deinstitutionalisation (particularly in physical and brain growth), although substantial impairment can persist for the most seriously affected children over the longer term.

The authors note other risks of institutionalisation, including the effects of children not being able to participate in social, cultural, economic and religious life in their communities, the vulnerability of institutionalized children to violence and neglect, and the role some institutions play in child trafficking.

Phasing out the institutionalisation of children

Continuing the use of institutionalisation means that these health and social costs will continue to accrue. It also runs counter to the benefits of deinstitutionalisation of child welfare systems, as well as the UN-recognised right of children to be raised in a family environment. In the second part of the Commission, published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health journal, the authors identified evidence-based policy recommendations to promote family-based alternatives to institutionalisation:

A global push for reform

Building momentum for change at the national level

Taking action locally

“These recommendations prioritise the role of families in the lives of children to prevent child separation and to strengthen families, to protect children without parental care by providing high-quality family-based alternatives, and to strengthen systems for the protection and care of separated children,” says co-author Beth Bradford, Changing the Way We Care, U.S..

Source: Read Full Article