The human heart is an intricate, complex organ and, like a car that starts sputtering, its function deteriorates for all sorts of reasons. Cardiomyopathy—any disease of the heart muscle that makes it pump blood less effectively—can be caused by blockages, thickened muscles, or enlarged heart chambers, among other things. For clinicians, differentiating and properly diagnosing these types of diseases can be difficult.

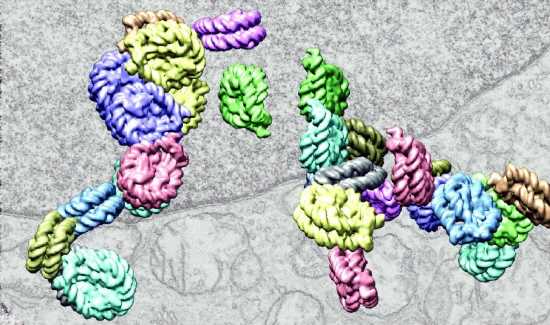

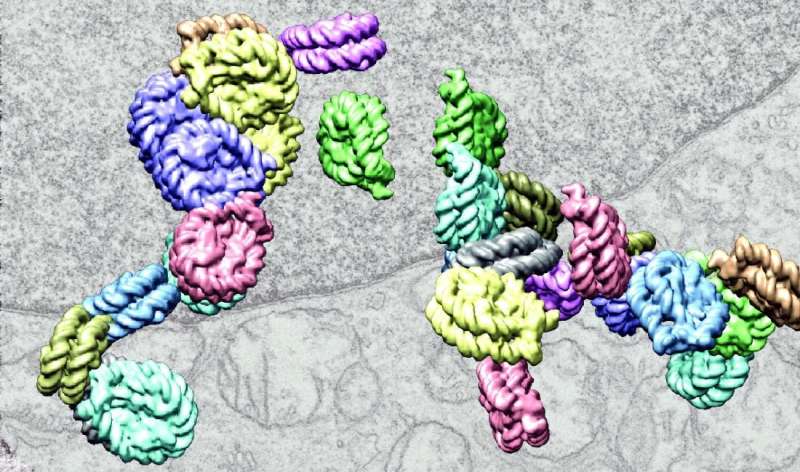

Now, an interdisciplinary team of clinicians and researchers at UT Southwestern has shown that some subtypes of cardiomyopathy can accurately be diagnosed by analyzing how molecules of DNA inside heart cells are organized into chromatin—the densely packaged structure of DNA. Changes to chromatin impact which genes are active in a cell and therefore can affect heart function.

“Being able to better diagnose cardiomyopathies makes a difference for not only guiding treatment but also informing patients of their prognosis,” said cardiologist Nikhil Munshi, M.D., Ph.D., Associate Professor of Internal Medicine at UT Southwestern and a co-senior author of the new work, published in Circulation.

When someone has symptoms of heart disease, such as shortness of breath, dizziness, or swollen legs and feet, doctors typically analyze their heart using tools like echocardiograms to gauge how the heart’s muscles and valves are working. If they suspect a blockage, they’ll turn to a coronary angiogram, in which dye helps visualize how blood flows through the heart. The results help guide what type of treatment—from drugs to heart stents—is best for any given patient.

About a quarter of the time, however, cardiologists can’t pinpoint any particular underlying cause for cardiomyopathy. Moreover, autopsies of heart disease patients have revealed that doctors often misdiagnose subtypes of cardiomyopathy.

Dr. Munshi, in collaboration with UT Southwestern surgeons, transplant cardiologists, and Gary Hon, Ph.D., Associate Professor in the Cecil H. and Ida Green Center for Reproductive Biology Sciences, analyzed cells from the left ventricles of 15 patients with cardiomyopathy as well as six healthy individuals. Since heart biopsies are not routinely performed for cardiomyopathy, the researchers used samples taken from patients undergoing heart transplants or myectomies (surgical removal of muscle tissue) and from healthy donor hearts.

They used a machine-learning approach to analyze thousands of sections of chromatin in each patient’s cells and pinpoint what differed between patients with three subtypes of cardiomyopathy—hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (caused by thickening of the left ventricle walls), ischemic cardiomyopathy (caused by blockages in coronary arteries), and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (caused by an enlarged left ventricle without underlying structural changes). The machine-learning program was able to recognize different signatures of the chromatin in each patient group.

“Chromatin is like a very unique fingerprint of the state of a cell,” said Dr. Hon. “This was a proof-of-principle study to show that we can indeed train an algorithm to differentiate these fingerprints between patient groups.”

To test the effectiveness of the program, the researchers used it on three new patient samples that hadn’t been included in the original sample. The program correctly identified the type of cardiomyopathy of each patient and showed that the chromatin patterns changed after treatment for cardiomyopathy.

The researchers said that since heart biopsies are not currently the standard of care for cardiomyopathy patients, there is no immediate path toward using the new data in the clinic. However, if chromatin patterns enable a drastically improved diagnosis of cardiomyopathy, it may encourage the use of biopsies.

Source: Read Full Article