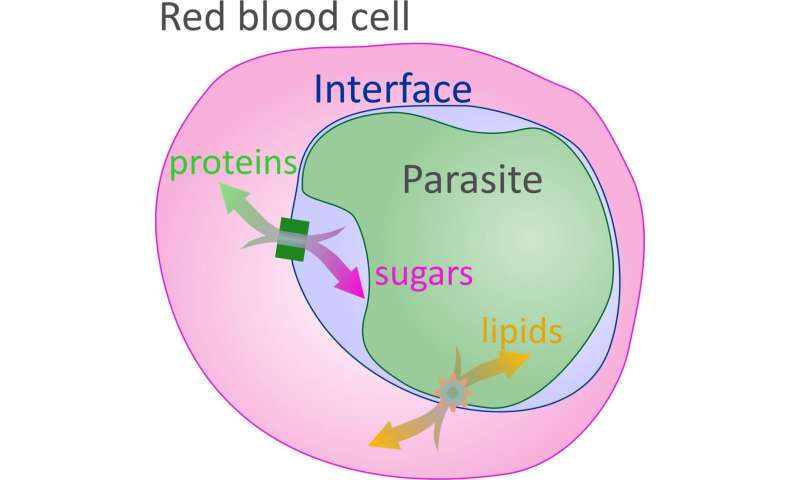

Researchers at the National Institutes of Health and other institutions have discovered another set of pore-like holes, or channels, traversing the membrane-bound sac that encloses the deadliest malaria parasite as it infects red blood cells. The channels enable the transport of lipids—fat-like molecules—between the blood cell and parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. The parasite draws lipids from the cell to sustain its growth and may also secrete other types of lipids to hijack cell functions to meet its needs.

The finding follows an earlier discovery of another set of channels through the membrane enabling the two-way flow of proteins and non-fatty nutrients between the parasite and red blood cells. Together, the discoveries raise the possibility of treatments that block the flow of nutrients to starve the parasite.

The research team was led by Joshua Zimmerberg, M.D., Ph.D., a senior investigator in the Section on Integrative Biophysics at NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The study appears in Nature Communications.

Source: Read Full Article