A new paper by researchers at the Center for Community Health and Development, an academic health department within the University of Kansas Life Span Institute, details their monitoring and evaluation of the COVID-19 response of the Douglas County public health system.

The findings were just reported in the peer-reviewed journal Health Promotion Practice.

As the pandemic was emerging, there was little understanding of the nature of local public health responses and what enabled them. The KU CCHD partnered with Lawrence-Douglas County Public Health and the Unified Command to better understand the local COVID-19 response.

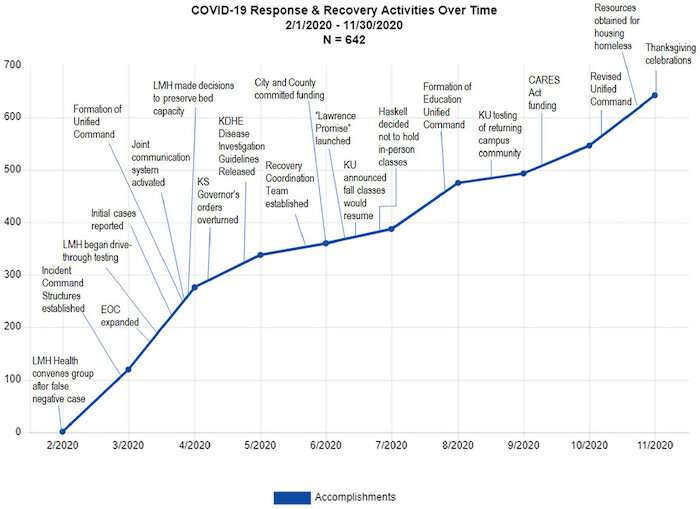

“My colleagues and I adapted our center’s monitoring and evaluation system to document and analyze the unfolding of public health measures implemented in Lawrence and Douglas County,” said lead author Christina Holt, investigator and director of training and technical assistance at the CCHD. “With funding from the Kansas Health Foundation, we documented and characterized nearly 1,000 local response activities and their contribution to bending the curve of new cases of COVID-19 in the community. By reflecting with local partners on factors associated with the pattern of cases, we developed a better understanding of local efforts.”

Key local partners in the COVID-19 response efforts included Lawrence-Douglas County Public Health, LMH Health, Douglas County Emergency Management, the Heartland Clinic, KU Emergency Management, Douglas County’s COVID-19 Unified Command, local school districts, the City of Lawrence, Lawrence Community Shelter, Family Promise and local nonprofits. Representatives from those groups met in sessions facilitated by the KU researchers to reflect on factors associated with increases or decreases in the patterns of new cases and response activities.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic started to spread in 2020, most communities had good surveillance systems in place to track new cases of COVID-19,” said co-author Stephen Fawcett, senior adviser at CCHD and Kansas Health Foundation Emeritus Distinguished Professor at the KU Department of Applied Behavioral Science. “But less information was available about the response—that is, the programs, policies and practices that local health systems were putting in place to respond to the changing pandemic. If we could construct a well-documented picture of the local COVID-19 response, partners would have more information to make adjustments. That’s what this case study tried to do.”

The most important findings of the center’s community-engaged scholarship addressed which COVID-19 response activities and events were related to increases and decreases in new cases in Douglas County, according to the stakeholders themselves.

The authors found several key factors associated with delaying the rise in cases from the initial worldwide outbreak: local school and university decisions to hold classes online after spring break; closures of recreation centers and libraries; a statewide stay-at-home order; and prohibitions of large gatherings.

Once COVID-19 cases were confirmed in Douglas County, authors cited three key factors for controlling the outbreak: forming a Unified Command structure for COVID-19 response; state and local stay-at-home orders; and changes in business practices.

But the subsequent lifting of statewide restrictions, outbreaks in bars and fuller reopening of businesses were associated with a rise in cases, the researchers determined. Factors that “bent the curve” following the uptick included Douglas County and statewide mask-wearing mandates and bar closings. Later in the pandemic, a second rise was seen locally that the researchers tied to KU students moving back to town and into congregate housing and KU mass testing for students, faculty and staff.

The study found this second rise was reduced by KU’s crackdown on fraternities not complying with COVID safety, a ban on alcohol sales in later hours, bar/restaurant inspections and a Lawrence City Commission ordinance to ticket COVID-19 regulation noncompliance. A KU cut in testing to a more targeted approach later in August may also have led to fewer cases detected.

The study found, “Ongoing factors include some K-12 schools opening, with varied compliance with public health guidance (e.g., allowing fall/winter sports). Factors associated with increased cases from September and continuing through November included social gatherings, athletics and inability to socially distance in congregate living settings.”

Ultimately, KU researchers, in collaboration with partners in the local public health system, sought to better understand the public-health response to the pandemic and to use this information to make adjustments.

“Our Unified Command partners—the City of Lawrence, Douglas County, KU, LMH Health, USD 497 and the Chamber of Commerce—were actively engaged in the sessions facilitated by the Center for Community Health and Development,” said Dan Partridge, director of Lawrence-Douglas County Public Health, who served as a co-author on the study. “I observed that these sessions helped all of us to take a pause and broaden our field of view. In doing so our collective sense of what works was sharpened and our ability to continue to improve was enhanced.”

In addition to Holt, Fawcett and Partridge, co-authors of the study were Ruaa Hassaballa-Muhammad and Sonia Jordan of Lawrence-Douglas County Public Health.

The KU team said they were particularly impressed with efforts of local public-health partners, including equity impact advisers of the Unified Command, to try to minimize the potential harm of public-health measures for those most vulnerable.

Source: Read Full Article