Skip to:

- Detection of Cannabinoid Incorporation

- Effect of Hemp Oil on Air

- Variability of Cannabinoid Concentrations in Hemp Oils

A team based at the University of Bournemouth have determined that topical application of is cannabis can result in cannabinoid incorporation – in the hair follicle. Through analysis of hair from 10 volunteers undergoing a 6-weeks topical treatment with commercially available hemp oi, the team determined that incorporation occurred in 89%, with three of the major constituents detectable in 33% of volunteers.

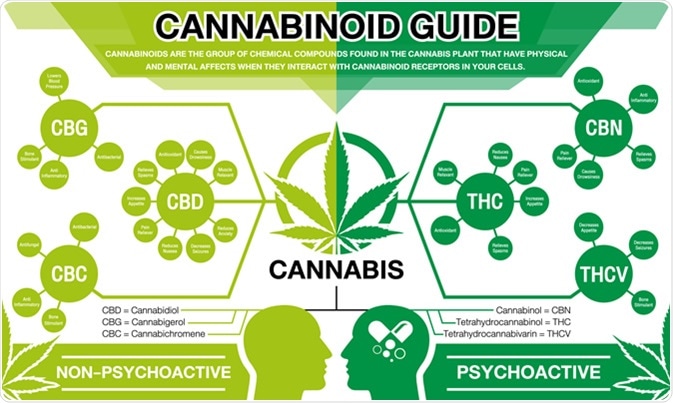

Traditional toxicology testing requires sampling of hair strands to demine recreational use of Cannabis. In addition to this (largely) illegal use, cannabis has widespread applications in cosmetics (hemp), medicine and textiles. Of the cannabinoids tested for, Δ (9)-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), [11-nor-Δ(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid (THC-COOH)] and two cannabinoids (cannabinol (CBN) and cannabidiol (CBD)) are tested for in particular. THC is the major psychoactive component of cannabis, THC-COOH is a metabolite, while both CBN and CBD are non-psychoactive cannabinoids.

Detection of Cannabinoid Incorporation

The presence of these constituents in the hair follicle of the subject is taken to infer recreational use. However, passive and other mechanisms of incorporation may also occur. Passive exposure has been evidenced; a recent study determined that, under confined conditions, detection of cannabinoids above threshold is possible. Higher concentrations of THC and THC-COOH were also found predominantly in the blood, urine and hair. There is an argument for the appearance of THC/CBN/CBD in hair occurring due to chronic exposure – as such the distinction between contamination and consumption is difficult. THC-COOH, however is one distinguishing metabolite; as it is only synthesized in the body, its presence unequivocally indicates consumption. In the laboratory setting expensive instrumentation and sample preparation precludes its use in routine testing of hair follicles. The overarching issue, then, is the consumption of hemp products potentially impacting on cannabis drug testing. The use of hemp oil in hair has been widespread, owing to unsubstantiated claims that it elicits both moisturizing and accelerated growth effects. The composition of these products varies, from pure to low-concentration hemp-oil products.

Effect of Hemp Oil on Air

Paul et al. investigated the effect of direct application of hemp oil to head hair – quantifying their results using cannabinoid measurements. Volunteers underwent a 6-week use period, applying hemp oil in the evening, following hair washing the following morning. Head hair samples from 10 volunteers were collected; one volunteer was excluded due to prior detection of CBD, THC and CBN prior to treatment. One third presentented with the three cannabinoid constituents following treatment. Relative to a comparative study by Taylor et al., in six of the volunteers, the cannabinoid levels are consistent with levels present in light recreational users of cannabinoids– alongside lower levels of the indicator-consumption cannabinoids THC-OH and THC-COOH. Hence risk of mistaken interpretation of light use in the case of topical cosmetic application could occur.

The team determined that presence of THC analogues where donors report hemp oil application may occur – although by implementing analytical criteria for analyte peak acceptance should sufficiently characterize these. Another notable finding was the presence of the metabolite THC-OH in the hair of a single volunteer. As this result from metabolization in the body, this finding suggested possible THC-OH presence in the hemp oil as the volunteer denied consumption or exposure to cannabis during the 6-week study period. Indeed, the level of THC-OH fell within the range determined in an earlier study that determined its level after cosmetic treatment. Thus, determination of both consumption-generated metabolites is recommended to unequivocally differentiate consumption from external exposure or contamination.

Variability of Cannabinoid Concentrations in Hemp Oils

A second notable point that Paul et al. described was the variability of cannabinoid concentrations in hemp oils – a corroborating study by Citti et al. determined that key cannabinoids across different oils ranged from levels below the limit of detection (LOD) to detectable ppm measures. In light of this, the team suggest that levels of cannabinoids that results demonstrated may vary as a function of the hemp oil used.

The team further explained the presence of THC, despite its absence in the har oil used; namely the decarboxylation of any Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA-A) possibly present. In addition, decarboxylation of an additional cannabinoid present cannabidiolic acid (CBD-A) could augment THC levels observed. An earlier study by Perrotin-Brunel et al. indicate that light or heat could induce decarboxylation of both cannabinoid; both conditions could have arisen via daylight exposure and use of a hair dryer, as Paul et al. speculate. In the absence of the team’s analytical method limitations in detecting these, it is plausible that hemp oil used in the study contained THCA-A and CBD-A. The analytical procedure for extraction of cannabinoids from hair may also induce decarboxylation – thus artifactually increasing THC concentrations. However, the methanolic wash procedure should have removed contaminants, thus this may not apply in the team’s study. Finally, THC-COOH was not detected in the hemp oil nor in the remaining 9 volunteers post hemp oil application.

The detection of cannabinoids in hair samples following cosmetic application, at levels comparable to cannabis exposure in some instances, is therefore a concern to Paul et al. Consequently, the team suggest ‘that cosmetic use of hemp oil should be recorded when sampling head hair for analysis, and that the interpretative value of cannabinoid hair measurements from people reporting application of hemp oil is treated with caution in both criminology and public health.’

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bournemouth University. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sources

- Citti, C. et al. (2018) Analysis of cannabinoids in commercial hemp seed oil and decarboxylation kinetics studies of cannabidiolic acid (CBDA). J Pharm Biomed Anal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2017.11.044

- Franz, T. et al. (2018) Proof of active cannabis use comparing 11‐hydroxy‐∆9‐tetrahydrocannabinol with 11‐nor‐9‐carboxy‐tetrahydrocannabinol concentrations. Drug Test Anal. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.2415

- Herrmann, E. S. et al. Non-smoker exposure to secondhand cannabis smoke II: effect of room ventilation on the physiological subjective and behavioural/cognitive effects. Drug Alcohol Depend. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.019

- Paul, R. et al. (2019) Detection of cannabinoids in hair after cosmetic application of hemp oil. Nature Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39609-0

- Perrotin-Brunel, H. et al. (2011) Decarboxylation of D9 -tetrahydrocannabinol: Kinetics and molecular modeling. J Mol Struct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2010.11.061

- Taylor, M. et al. (2017) Comparison of cannabinoids in hair with self-reported cannabis consumption in heavy, light and non-cannabis users. Drug Alcohol Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12412

[Further Reafing:Cannabinoid]

Last Updated: Sep 3, 2019

Written by

Hidaya Aliouche

Hidaya is a science communications enthusiast who has recently graduated and is embarking on a career in the science and medical copywriting. She has a B.Sc. in Biochemistry from The University of Manchester. She is passionate about writing and is particularly interested in microbiology, immunology, and biochemistry.

Source: Read Full Article