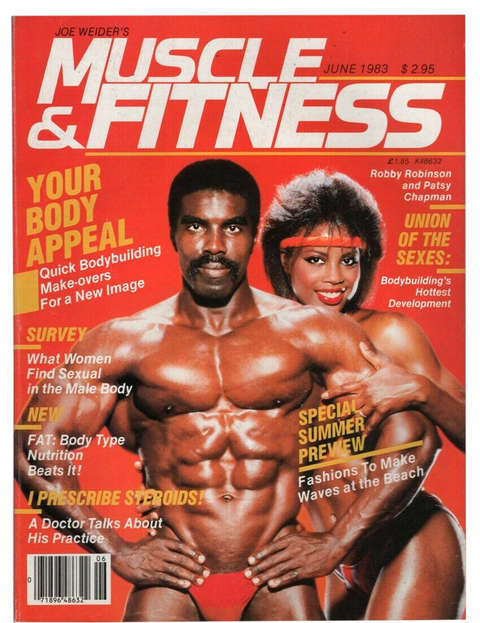

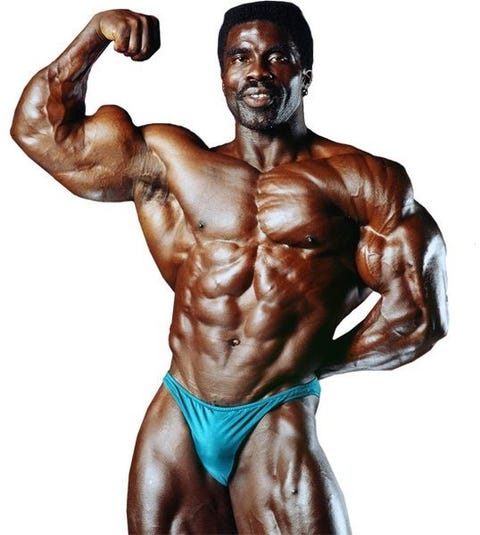

WHEN ROBBY ROBINSON started bodybuilding at Venice Beach’s Gold’s Gym in 1975, he remembers being told “Blacks don’t get contracts” to compete. He was harassed at contests and struggled with steroids and sickle cell anemia. Despite many wins, Robinson never captured the IFBB’s overall title, Mr. Olympia. After he complained about mistreatment, the IFBB suspended him and he moved overseas to compete without the fear of racism. He’d eventually return to the U. S. in 1994, winning the first-ever Masters Mr. Olympia, for athletes over 40, and then two more Masters titles in his 50s. Today, at age 75, Robinson still lifts, and he shares how he forged the strength to face any challenge.

MAKING THE LEAP

I WENT TO what was basically an all-Black high school in Tallahassee, Florida, so I really didn’t encounter that much racism. Because everybody was poor, Blacks and whites, it didn’t look like I was any better than you—we ate the same food, cooked in the same pots. So I didn’t really get a blunt force of it, I guess, until I left the swamps. I never heard the word n***** until I came to California in ’75. When I left the swamps, I realized, Wow, life is gonna be hard out there. That’s how I dealt with it.

BLOCKING OUT BIAS

I WAS DOING well because I had just a great body. I mean, that’s just the hardcore facts. I had a great physique; I had a good, tough mindset. So I just didn’t listen to all the negs. I think when you get caught up in the negs and just keep listening to it, it drains your ability to do whatever you want to do positive. I just didn’t pay any attention to it.

BATTLING OTHER DEMONS

MY FIRST ENCOUNTER with steroids was about two weeks before Mr. World [in 1979]. I remember taking a shot, walking home, collapsing in the door. My lady friend dragged me in the house. I collapsed because of the fact that when you take steroids, [there can be blood-pressure issues]. And for a person that has sickle cell, like I do, that’s just not good. So I was getting no oxygen to the brain, no oxygen to the heart; I’m almost probably going into a cardiac arrest. She was able to drag me to the bathtub and put cold water on me. Now, you might not believe it, but that saved my life. I went to New York and won Mr. World two weeks later, and I’m thinking, This is madness!

EXPERIENCING INJUSTICE

WHEN I CAME to Los Angeles in 1975 from Florida, I was denied a professional contract. By the ’80s, I’d moved to Europe, and I was based there basically my whole career, almost 13 years. Over there, I was treated completely differently. I was able to work and do exhibitions and seminars. I made enough money to buy a little home in Holland. So I think, Something good, something bad—that’s just how life is. It’s not perfect; it didn’t make you any promises. You have to go in there and make life, whatever life you want, all on your own. Nobody’s gonna give it to you. It inspired me, bro. I just kept working.

STAGING A COMEBACK

I CAME BACK in 1994 for the Masters Mr. Olympia. I was standing onstage and they announce, “The first Masters Mr. Olympia winner 1994, Robby Robinson.” I remember all the obscenities I was called. I remember hearing all the fans—everybody booed. After the judging, after the show was over, they normally have a big banquet, and that night there was no banquet, there was no party, there was nothing. That hit me hard. And you’re talking the auditorium is packed, thousands of people screaming and yelling, you know, for Lou [Ferrigno]. But when the judge said, “The first Masters Mr. Olympia is Robby Robinson,” everybody let out boos.

BECOMING MORE VOCAL

YOU CAN’T BREAK me down mentally; the only person who can break me down is myself. And I just never listened to the negatives. For the Masters Mr. Olympia, I knew that if I could go in there and get myself in great shape, that whatever competitors—whatever racism, discrimination was there—I thought my physique could take it down, and it did. I made it through all of that, and I just felt that you got to say something. [In the early ’80s] I was suspended because of the fact I’ve spoken out about “Hey, you know, listen, there’s really no money here; people don’t really care about you. If you don’t care about yourself, you’re not gonna make it.”

STAYING READY FOR WHATEVER

YOU HAVE YOUR wishes and dreams, like to go to Hollywood and be labeled into that world, like Arnold with Conan and Lou the Hulk. I thought it would be a great thing to do. But naaah, they weren’t ready for that. You know, out there in that world at that point at that time, those doors were just not open. Today I’m in the process of doing a documentary on my life. I don’t really have the desire to want to be a movie star now. But if someone came along and said, “Hey, listen, run over there and jump over that wall and fire your machine gun,” I’d give it a try.

CONTINUING TO DO THE WORK

NO DISRESPECT TO any of the guys that are out there trying to create a great physique, but I don’t see it as art anymore. I just see big bodies out there that are all just a large amount of anabolics and whatever else they can use to get that physique. And you know, I can’t admire it. I’m in a very happy place with what I’ve accomplished. Hard work pays off. I continue to say that.

Robbie Robinson was interviewed and photographed for Lift Every Voice, in partnership with Lexus. Lift Every Voice records the wisdom and life experiences of the oldest generation of Black Americans by connecting them with a new generation of Black journalists. Robinson’s interviewer, Kristian Rhim has written for Men’s Health, The Undefeated, and Philadelphia magazine. The complete oral history series is running across Hearst magazine, newspaper, and television websites around Juneteenth 2021. Go to oprahdaily.com/lifteveryvoice for more.

Turn Inspiration to Action

Consider donating to the National Association of Black Journalists. You can direct your dollars to scholarships and fellowships that support the educational and professional development of aspiring young journalists.

Also, support The National Caucus & Center on Black Aging. Dedicated to improving the quality of life of older African-Americans, NCCBA’s educational programs arm them with the tools they need to advocate for themselves.

Source: Read Full Article