Despite having an estimated two times higher risk of death than white Americans from the COVID-19 pandemic, Indigenous people in the U.S. and Canada experienced surprisingly positive outcomes––they exhibited an impressive collaborative strength.

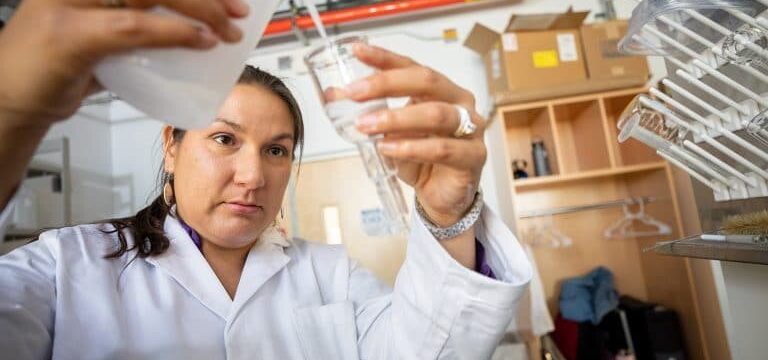

Principal investigator Naomi Lee is the first author on a recent publication in The Lancet Infectious Diseases that demonstrated Indigenous people have the ability to thrive anew.

In the article “Infectious Diseases in Indigenous Populations in North America: Learning from the Past to Create a More Equitable Future,” authors from Northern Arizona University, the University of Saskatchewan in Canada and Johns Hopkins University used Indigenous data from a variety of search data and publications through Dec. 31, 2002, to examine the ongoing effects of colonization on Indigenous people, specifically in the historical context of infectious disease.

Their goal with the publication was to improve health equity among Indigenous populations—the idea that everyone can be as healthy as possible. Through their work, they found that reclaiming health for Indigenous people is directly tied to reclaiming and promoting Indigenous ways of understanding the world and interacting in it.

“The COVID-19 pandemic showed colonization is still impacting Indigenous populations in North America,” said Lee, who is Onödowága (Seneca Nation of Indians from western New York state), assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry at NAU. “Collectively, we felt it was important to acknowledge these effects while proposing a framework to improve the health of Indigenous people. We also wanted to present culturally informed case studies the authors use to address the communities’ infectious diseases.”

Improving health equity for Indigenous people through colonization acknowledgments

The researchers found that Indigenous populations’ infectious disease health trajectories can improve when governments and institutions commit to respecting Indigenous wellness models, acknowledging and ending ongoing colonization, practicing cultural humility and strengthening health care services.

Their publication also calls on governments, public health leaders, industry representatives and researchers to reject harmful research practices and adopt a framework for achieving sustainable improvements in the health of Indigenous populations “adequately funded and wholly grounded in respect for tribal sovereignty and Indigenous knowledge.”

“The framework for attaining sustainable improvements in Indigenous People’s health proposes ways for the government, health care providers and community to address health care through cultural humility,” Lee said. “This includes respecting tribal sovereignty, committing to self-reflection and strengthening the community.

This framework would create sustainable improvements in Indigenous people’s infectious disease health, including advances in biological, behavioral, environmental and structural interventions; community education and disease prevention; Indigenous research capacity and data sovereignty; and high-quality local data on disease burden and disease risk factors.

“In addition, we recognized that efficacious vaccines can receive infectious diseases, but to achieve equity, must respect the holistic approach to health; thus, we presented case studies to emphasize the impact of cultural humility on the respective communities,” Lee said.

Infectious diseases among Indigenous started with colonization

In their publication, the authors examine the history of contagious diseases among Indigenous populations throughout the U.S. and Canada and the common risk factors directly tied to colonization’s ongoing effects.

According to the researchers, colonization that began in 1492 was not a single event that happened long ago but is an event that “happened in waves, over time, leading to coloniality—a living legacy of interconnected systems that perpetuates settler colonialism.”

They also examined atrocities in biological warfare, such as colonizers’ distribution of smallpox-infected blankets and medical experimentation. They forced sterilization, along with other infectious and bacterial disease exposure that colonization brought to Indigenous people, contributing to the ongoing experiences of mistrust, intergenerational trauma and historical trauma.

They found that structural oppression and colonization, which resulted in the loss of language and culture, environmental deprivation, racism and disconnection from the land, are prime contributors to poor health outcomes in Indigenous communities.

“We want researchers and government agencies to acknowledge the continued effects of colonization and assimilation on Indigenous populations,” Lee said. “We also come together to implement change through laws, policies, cultural humility and sovereignty to address these effects and improve health in Indigenous populations.”

More information:

Naomi R Lee et al, Infectious diseases in Indigenous populations in North America: learning from the past to create a more equitable future, The Lancet Infectious Diseases (2023). DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00190-1

Journal information:

Lancet Infectious Diseases

Source: Read Full Article