Large events are cancelled, restaurants and non-essential businesses are closed, and in many states, residents have been asked to shelter in place, all to limit the spread and impact of the COVID-19 virus. But are strict and early isolation and other preventative mandates really effective in minimizing the spread and impact of a disease outbreak?

Stefan E. Pambuccian, MD, a Loyola Medicine cytologist, surgical pathologist and professor and vice chair of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, has reviewed published data and research from three papers dating back to the 1918-19 Spanish flu pandemic, which infected one-fifth to one-third of the world’s population and killed 50 million people.

According to the data and analysis, cities that adopted early, broad isolation and prevention measures—closing of schools and churches, banning of mass gatherings, mandated mask wearing, case isolation and disinfection/hygiene measures—had lower disease and mortality rates. These cities included San Francisco, St. Louis, Milwaukee and Kansas City, which collectively had 30% to 50% lower disease and mortality rates than cities that enacted fewer and later restrictions. One analysis showed that these cities also had greater delays in reaching peak mortality, and the duration of these measures correlated with a reduced total mortality burden.

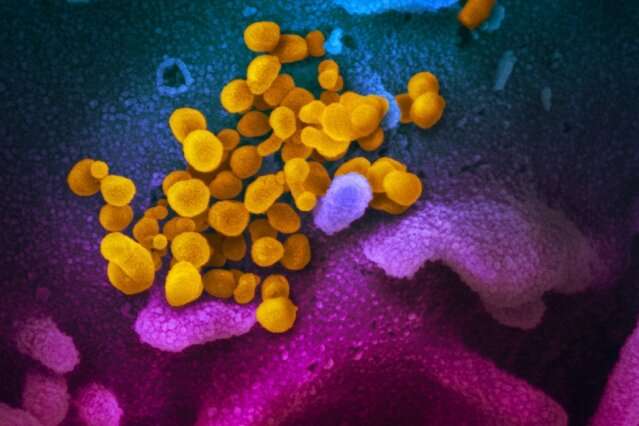

“The stricter the isolation policies, the lower the mortality rate,” says Dr. Pambuccian. He studied the Spanish flu, including prevention measures and outcomes, to help develop standards for staffing and safety in the cytology lab, where infectious diseases like the COVID-19 virus are diagnosed and studied at the cellular level. His broader article appeared online this week in the Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology.

Like today, not everyone in 1918 and 1919 thought the strict measures were appropriate or effective at the time.

An estimated 675,000 people died in the U.S. from the Spanish flu, “and there was skepticism that these policies were actually working,” says Dr. Pambuccian. “But they obviously did make a difference.”

In 1918, the world was still at war “with overcrowded barracks,” and much of the U.S. lived with “poverty, poor nutrition, poor hygiene, household/community-level crowding, and a lack of preparation of the population and decision makers due to cognitive inertia and poor medical and insufficient nursing care,” says Dr. Pambuccian.

Source: Read Full Article