Take a nice, deep breath. Now imagine your lungs: Myriad airways like branches, each with tiny alveoli-like leaves. This alveolar structure is key to the absorption of oxygen and excretion of carbon dioxide that we call “breath.” As we breathe, the volume of gases in the lungs is continually changing with varying degrees of inhalation and exhalation. These volumes are medically important for clinical assessment and diagnosis of respiratory pathologies.

A light-based technology known as gas-in-scattering-media absorption spectroscopy (GASMAS) may allow noninvasive optical sensing of respiratory volumes. Using tuneable diode laser spectroscopy, GASMAS turns optical signals into information for measuring gas concentration. Reference models, known as “phantoms,” afford relevant features that help biomedical optics researchers to identify technical challenges and potential applications of GASMAS technology.

As reported in the Journal of Biomedical Optics, scientists at Tyndall National Institute (TNI) in Ireland recently developed a lung phantom that mimics the optical properties and structure of the lung, including the tiny alveoli. The complexity of alveolar anatomy has meant that previous state-of-the-art lung phantoms have neglected it. The work done with this novel lung phantom demonstrates the feasibility of GASMAS to sense changes in gas volume in a controlled environment mimicking lung tissue.

Previous work toward clinical use of GASMAS for respiratory healthcare has focused on neonates, because the thickness of protective organs surrounding their lungs is within the limits of penetration depth for near-infrared light. According to first author Andrea Pacheco, a Ph.D. student in the Biophotonics@Tyndall Group, the extension of GASMAS technique beyond neonates will depend on advances in miniaturization and integration of pulmonary endoscopes with GASMAS probes. “A further step in that direction could be to arrange two miniature GASMAS probes in an endoscope-like geometry and use our phantom to determine the signal quality and optimum source–detector separation,” she says. Pacheco and her coauthors show the basic principles involved in recreating lung tissue. Future researchers can vary the dimensions or density of the gas pockets simply by designing a new capillary holder and using capillaries with different inner radii.

Lung phantom challenges

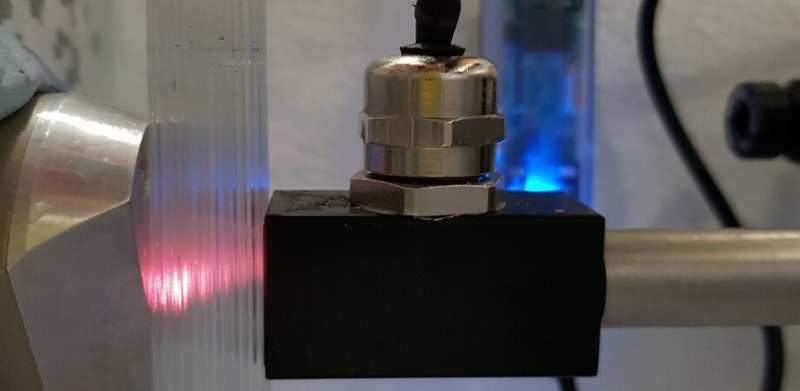

To mimic alveoli, the novel lung phantom developed by the TNI Biophotonics team features a system of capillaries that can be variably and progressively filled with liquid that matches the optical properties of lung tissue, allowing incrementally variable pockets of air that mimic air-filled alveolar sacs. Light transmission corresponds to the capillary content in a way that’s analogous to lung inflation and deflation. This all takes place within a carefully controlled environment that mimics the humidity and temperature of the body, typically maintained at around 37 degrees Celsius.

According to Pacheco, the challenges involved in creating a relatively complex model of the lung for clinical use required significant investments of time and energy: “The clinical translation of existent technologies is tremendously challenging. The work related to this article started two years ago.” The most difficult part of the work was the need to mimic body temperature and relative humidity in a controlled manner.

Pacheco says, “It was frustrating simply trying to maintain a temperature of 37 degrees Celsius inside a bottle half-filled with water. No matter what I tried, I did not manage to do two consecutive GASMAS measurements with the same (or at least similar) parameters. And if this was just a bottle, how was I supposed to move from there to recreate lung tissue?”

Source: Read Full Article